This interview is part of Anchor Editorial, a collaboration between Sixty Inches From Center and Anchor Curatorial Residency. This five-part series is co-created and written by Carlos Flores, this year’s Curatorial Resident, and Tiffany M. Johnson, who co-designed the residency with the Chicago Park District and was Anchor’s 2022 Curatorial Resident. Together, they will be publishing conversations with fellow curators, artists, and collaborators, as well as experimental essays and archive dives that explore the topics that impact their curatorial practices.

Anchor Curatorial Residency offers an 18-month journey to explore collective ways of being on the neighborhood level. In this residency, artists and community members engage in a unique creative process to deepen connections and forge new relationships. The Curator-in-Residence receives space, time, and resources to enhance their curatorial practices, producing a collaborative, community-based exhibition rooted in experimentation, local knowledge, and everyday experiences.

A program of the Chicago Park District, Anchor Curatorial Residency brings local talent together to build reciprocal relationships with neighbors and stakeholders, collectively activating public spaces. Through this program, the Chicago Park District promotes resource sharing and educational exchanges as essential practices for the health and well-being of Chicago.

On Friday, March 29th Carlos Flores and Tiffany Johnson sat down with artist Sonja Henderson in her MANA studio to discuss her art practice, public space, and curation. Sonja Henderson is a sculptor, mixed-media artist, teacher, collaborator, and innovator based in Chicago, Illinois. Her work explores the organic nature of spirit, joy, and grounded connection through Restorative Justice practices.

Carlos Flores: We were hoping to first acknowledge where we are—your beautiful studio. I think both of us are aware of your work through the [lens of] restorative justice and monumental interventions in public space. And, this is just my thinking Tiffany, but when I’m here, I feel like this is a microcosm of Sonja’s activations in public space. I see a lot of color. I see a lot of volume and mass. It also feels like a very warm landscape.

Tiffany Johnson: It feels very homey for me, like the type of creative playground I would’ve wanted when I was younger—and as an adult, too. (laughs) I wanna explore.

Sonja Henderson: Thank you, I love that. That is pretty much my ethos. I am a teacher as well, and I love putting materials out there for people to explore, [to] stimulate curiosity. There [are] altars everywhere [and] lots of crystals and feathers. I surround myself with things that I love and that make me feel good.

TJ: Sonja, when we met last time, we had a conversation about how people know, define, and categorize your work, but how do you describe your work and why you do the work you do?

SH: I would describe my work as sacred placemaking, healing justice practice, and ritual object maker. When creating cast or mixed-media sculpture, many times I will get an impression or a vision of what the sculpture is by holding and getting a sense of the material, then manipulating it. I don’t have a long drawn-out process of creating sketches or renderings before touching the actual materials. I respond intuitively and directly to the materials and perceived form. That gold figurative sculpture called The Oracle with the headdress was envisioned as I was running across the street on Randolph and Michigan Avenue. I spotted a rusty fallen hubcap, picked it up, and The Oracle was already created. I immediately went to the studio and started modeling the head to go under the hubcap headdress or crown. As I further worked on The Oracle, the gilded hovering body and Afro-futurist adornment came to me through my connection to materials and my “downloading” process.

SH: The Mamie Till-Mobley and Emmett Till Memorial was a bit more challenging for me and my process because, with any historic figurative monument, the portrait, in particular, needs to be accurate and readable from all angles. Most sculptors start with an intense series of drawings and measurements to really flesh out the mathematics and design of the face and figure. My process is very different. For the Mamie Till-Mobley and Emmett Till Memorial, my spirit needed to sit quietly and for a very long time with the content, historic photos, family heirlooms and objects, and the conversations with close relatives. From that, I would receive downloads or a way to proceed in clay to tell their stories in the form of a figure and podium. Many of my drawings of Mamie and Emmett Till were created for the Till family and Argo Community High School (who commissioned me) to connect with the studio process, not necessarily for me to use as a reference or sculpting guide.

I am an artist that works very closely with communities to develop content and connection to their public artwork. After talking for hours at the Emmett Till Community Center in Summit, IL and presenting dozens of preliminary ideas for the Till Memorial—at the last minute, of the last day, of the last charette—Reverend Wheeler Parker (Emmett Till’s best friend, cousin, and witness to Emmett’s nighttime abduction) says to me, ”You know, Mamie’s favorite pastime was fishing; Mamie and Emmett spent most of their free time fishing and swimming at the fishing hole.” At that moment I knew exactly what the narrative tableau around the podium would look like. I received a snapshot in my mind of the “Boyhood” bas-relief tableau, which is very similar to the Anchor Curatorial Residency site behind Marquette Park field house—with the shoreline, trees, and elegant cranes standing one legged on stones while people fish. I had a similar experience while sculpting Mamie Till’s portrait and pleated skirt. My studio process consists of a lot of meditation, turning inward, and just listening to the messages that present the next steps.

TJ: When we invited you to this [conversation], Sonja, we wanted to engage an artist who not only had a public practice but was very clearly engaged deeply in the community. For me, curation is a research, exploratory, and political tool. For a very long time, I could not find spaces where I could use it as that. I also lean more into working “underground” than in the public eye. 2021, was the first time in years I engaged in public-facing creative work.

Myself, [along] with the Cultural, Arts, and Nature (CAN) team with the Chicago Park District, worked together to design the Curatorial Residency in 2021. Then I became the inaugural Curator-in-Residence in 2022. What excited me was pushing my understanding of what art and art engagement look like through communal ownership and buy-in. When working with the artists, one of the goals was to challenge our understanding of safety and accessibility and then how it shifts in public spaces based on identities and perspectives. It was space to start anew again. And that’s why I named my [curatorial project] Finding Ceremony. It was a place to practice getting it wrong and trying again together. We explored our understanding of ownership–ownership of public art, materials, and space. We asked each other questions like, how are you making offerings to this community? Considering who and what is already here.

SH: That’s wonderful—so many great points there. I also consider myself as an artist working underground. My practice is very quiet and intentional. Much of my work is spent listening to the people and their communities—what their desires and needs are for the artwork or space being created. I am finally beginning to surface, come above ground with my social practice and to network. And, networking actually does pay off, lol, because it helps make your vision sustainable. I never understood networking in the form of trading business cards and handshaking but in its truest sense it is a tool for building worlds of like minded people and communities that have a similar vision, language, and ability to uplift you through empathy and alignment. After coming above ground, I’m learning that being a part of a network like Anchor Curatorial Residency, you [Tiff] and Carlos offer renewed sources of energy, funding, critique, vital connections to artists and collaborations, and emotional and physical support. That being said, a social practice is very outward presenting, which is the community engagement, but it takes so much internal work and reflection in order to truly be connected with the community you are working with. So Tiffany, I can understand how you felt like most of your work was underground because so much of curatorial justice, restoration, and healing work is done through spiritual channeling, research, writing, and preparation for the communal and connective aspect of the work being done. You are truly doing the work when considering intersections between: ownership, access, materials, space, engagement, politics, and voice.

TJ: Do you mind giving us a quick summary of what [your] Mother’s Healing Circle [project] is?

SH: I founded the Mother’s Healing Circle in January 2020 for mothers who lost their children to violence. Mothers Healing Circle (MHC) often gets misinterpreted as a group against gun or gang violence, which it is not. These are mothers whose last vision of their children was a senseless violent act perpetrated in public. Many of the mothers’ children were innocent bystanders killed by gun violence, but we also have mothers whose children died from medical and vehicular violence. MHC is a group that helps restore mothers who have experienced the traumatic loss through the visual and meditative arts, holistic, and ancestral healing modalities. My mission is to try to relieve and release the trauma associated with grieving and loss—knowing that loss is a part of our growth on this planet and the world we’re living in, but to alleviate the suffering.

MHC holds space weekly for mothers with a shared experience. MHC is a curated healing gathering space where mothers and families can talk freely. This life affirming nonjudgmental space allows for the expression of feelings and emotions from song and praise, to the ”letting of water,“ laughter, and joy. MHC understands the necessity for expressing a deep range of emotions while grieving and recovering, offering nurture and support throughout the process. Most of the mothers experience racial and housing discrimination, surveillance and over-policing, face poverty and food insecurity, and live in fight-flight mode, which is destroying their adrenal glands. This along with the loss of their child is making them mentally, physically, and emotionally unhealthy. So under these conditions, how does one recuperate, recover from, or even rest after such a traumatic loss? The Mothers Healing Circle has taken on the responsibility of communal care for our mothers, to rejuvenate them, bring new life and vitality to the surviving family, and build a stronger community through this action.

After 4.5 years of weekly meetings, legacy projects, and holding safe space, the mothers are physically stronger, healthier, and more emotionally stable. I’m currently processing my own traumatic loss. I didn’t experience loss from violence, but I lost three people in my family within one month. While experiencing the loss and during the grieving process, we seem to be having an out-of-body experience. The mind seems to split and the body or central nervous system is in shock most of the time– making it very hard to do anything but grieve. The mind and body don’t really have the capacity to do anything but rest, which is why community care is essential as a healing modality. Grief, loss, and trauma are private experiences but the remedy is communal–it’s a communal activity of sharing love, support, and commonality. Grief is not supposed to be isolating, unbearable or life threatening, it is a way to teach us the greater gift of universal connection, sympathetic vibration, community, and self-care.

CF: What you’re doing is curating these spaces—that’s almost a medium.

SH: My medium is actually pulling together these spaces that create something, or gathering elements that create a particular energy or vibration, like an alchemist. So whether it becomes a final product, like the Mamie Till-Mobley and Emmett Till Memorial cast in bronze, or to express themselves release pain, suffering, and trauma, it is all the same kind of work to me.

CF: I think art can create those collective healing experiences. Art can do that seeping through membranes and really getting to complicated junctures of trauma. When you think of the amalgamation of these traumatic experiences and the horrible things that are happening in the world, art can help us hone in on the abstract energy that can come from beautiful collaborations.

Tiffany, this point makes me think of the inaugural Anchor [Curatorial Residency]. Would you mind sharing a little bit about the overarching themes that drove your curatorial framework the first year? I think one of them was really thinking about existing space safety and surveillance.

TJ: I think ownership is one [thing] that I’m often working through. It shows up on a larger, systematic, scale and trickles down to the community level. Black folks do not feel safe and comfortable in public spaces. That was at the core [of my thinking during my Anchor residency], as a person who does not feel safe in public spaces. But on the other hand, private doesn’t always equate to safe. I was playing with our ideas of safety and security. The Residency is based in parks, spaces, and places that are supposed to be safe for everyone, but that’s not always the case.

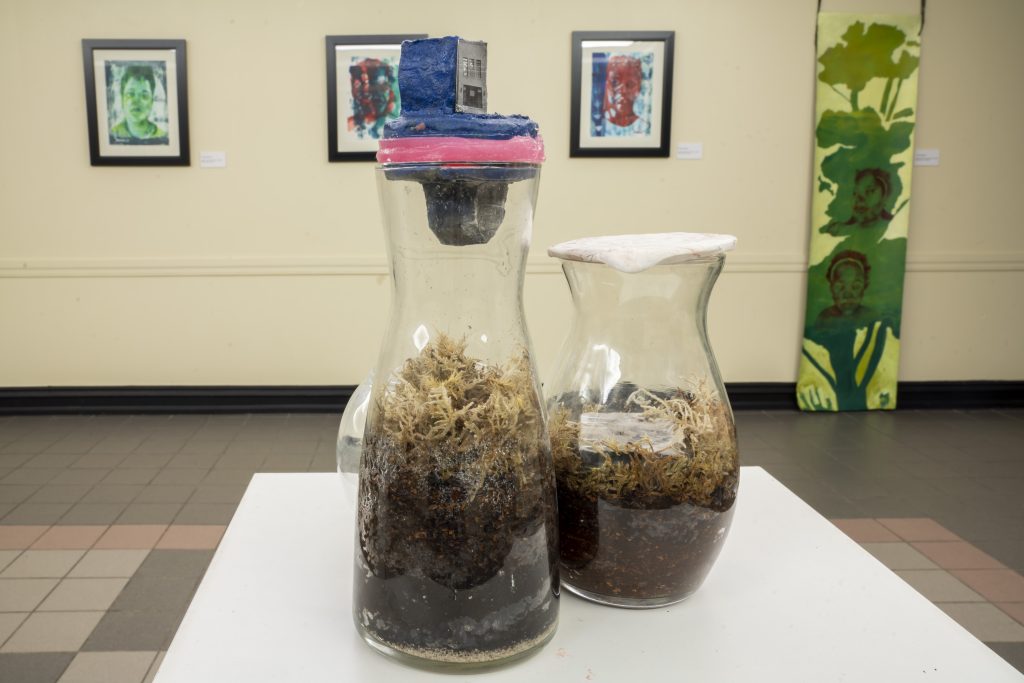

My installation attempted to invite new and alternative practices and rituals. Centering and considering the large ecosystems, including the land. I do think that will strengthen our relationships as humans. I was hoping Finding Ceremony, [the title of my installation during my Anchor residency], was one of those projects that encouraged that a little bit more.

SH: That’s so beautiful. So brilliant. Exploring the built environment, landscaping, creating sculptures, and getting our voices out there is incredibly important. And one of the questions that Carlos wrote down was: what are the origins of the ways we build things? I honestly think that we lean into the future a little bit because we are given so little access.

I love what our people, the Indigenous people are coming up with and putting on this planet and bringing into communities. I think it’s incredibly valid and always surprising and very visionary, and we need to see more of it. Then as the world sees more of our art, architecture, and imaginings, they might actually develop language around it. You know what I mean? It’s hard to speak to things that you’ve never seen or heard about before. As a teacher, I had to build a vocabulary around every project and technique. If we were sculpting, it came with a whole range of tools, practices, methods, and techniques, and you need to learn the language around that. So when a person walks up to your sculpture in an environment that they’re not used to seeing, that’s a very new experience for them. It is important that everyone has some tools and vocabulary to engage with art, the old and newly-built environments. I would say that having compassion for everyone and everything is one great tool and another is having discernment or context. Most often we have a programmed response to everything and it is important to slow down and sit with something before reacting.

And Tiffany, back to your point about safety and surveillance, BIPOC people and children have the human right to live, work, and travel safely. There is no reason for our people to be surveilled or harmed in any way while living our lives, playing, or even resting in our homes. This pathological behavior stems from supremacist thought and ends with profiting off our incarceration and genocide.

CF: The point [you’re making about] a lack of language or a surplus of language puts me in a similar framework to when I think [about] Finding Ceremony. You (Tiff) were operating outside of the traditional display. It was not creating a solution or making an assertion of any kind, but creating an ecology of interventions that would nourish those that would come there. You were creating this membrane of experiences for park goers and community members to be immersed in and feel connected to. And I think that’s a framework that will continue to shape the Anchor Curatorial Residency moving forward.

TJ: Carlos, One of the intentions you have with your Curatorial Residency right now is trying to figure out how to be a part of breaking cycles of stress. So I wonder if you could speak to that.

CF: I would love to. As we reflect more and more, Anchor is still an evolving initiative, a momentous experimental project that we are still learning a lot from. Anchor is very much about public space; it’s about allowing for regulation to happen for everyone who’s involved. In breaking the conventional gallery space, so much more has opened up experientially, but also internally. Being outdoors creates a lot of opportunities for pause and [it] resists a sort of mental and bodily numbing that we’re all victims of. And this “de-numbing” is one of the key intentions driving the Residency this year. How do we break out of the allostatic load of everyday life or the drudgery of everyday life unique to Southwestsiders [of Chicago]: a cumulative stress held by hard-working families balancing multiple jobs, family obligations, and immigration statuses? This is compounded by environmental stressors, like police violence and surveillance, environmental racism, and other inequities absent in more affluent Chicago areas. I was introduced to this kind of scientific term through a photojournalist and friend Sebastian Hidalgo, who is someone actively documenting environmental racism on the Southwest side of Chicago from a scientific perspective. The central point of it is environmental pollution—the disproportionate amount of particulate matter in the air. It’s also immigration status.

It’s over-policing, it’s surveillance, it’s increasing environmental hazards. It’s, particularly in the south or Southwest side, which is where the Residency now is happening. How can art or socially participatory projects really help the Marquette Park and Chicago Lawn neighborhoods break out of this chronic cycle of stress through the particular interventions that we’re all collectively planning for this year?

SH: That’s such a big question that we’ve been addressing from the beginning of the interview. So I’m just going to quickly go back to the Mother’s Healing Circle and our MHC Wellness Kits boxes, which are a part of our community care practice. The reason I bring this up is because, as you go through each product in the Wellness Kit, the user has a nourishing experience. First, creating the products in the Kit is a meditation for the mothers, a way for them to heal. We need curated spaces where our people can relax, feel safe, and not feel burdened. The recipient of a Wellness Kit has an immediate sense of ease and relaxation due to the herbs and elements inside: lavender, rose, honey, and cocoa butter. When using a product like the lotion bar, you are rubbing it on your skin and automatically giving your body self-love, self-care, self-massage. The Wellness Kits are personal tools of resiliency, healing, restoration.

Let’s talk about Marquette Park and the MLK Living Memorial. This monument—sculpted by myself and John Pittman Weber—is dedicated to movements that inspire equity, justice, and resilience to oppression. In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. lived and marched in Chicago to support a grassroots movement called the Fair Housing Marches. Peaceful people marched for the right to fair and equitable housing, against Redlining, surveillance, police brutality,and discriminatory policies. Fifty-five years later, I have erected a beautiful placemaking memorial to reflect history, and Anchor Curatorial Residency is creating an intersectional space curated by the new diverse community while addressing the same issues. Finding commonality is essential; it makes building and living together easy. I find the elephant in the room to be the absolute denial of discriminatory policies toward all BIPOC and lower income people, the lack of humanity and human rights policies, and the building of wealth through carceral and genocidal policies.

Like with you [Carlos and Tiff] and Anchor Curatorial Residency, John and I led with humanitarian ideals and inclusion while holding design workshops and charrettes with the people. Every aspect of the MLK Living Memorial considers the land it was built on and its blood soaked history, its connection to the community and human spirit, and our relationship to the cosmos. The plaza and walkway is a procession and reflects the Milky Way Galaxy we live in, the stele [3 carved pillars] tells the story of struggle leading to the now Beloved Community, and the architecture is surrounded by native nourishing plants cared for by neighboring agencies and formerly incarcerated people. Did you know there is actually a design concept called Hostile Architecture? This urban design strategy is a product of rampant supremacist patriarchal culture that punishes poor and disenfranchised people while entraining new public behavior and policy. I think it is incredibly important to hear all stories, seek new designers from all walks of life, and to apply new visionary concepts from BIPOC peoples.

CF: On that point, what’s unique about this residency is that it’s very relational to the specific social domains that we’re engaging in. First in Austin and now on the Southwest side of Chicago at Marquette Park, [which is] sandwiched between two neighborhoods: Chicago Lawn and Marquette Park. I’m just so honored to be [a part of] this collaboration with the Park District, colliding or threading with so many different communities that we kind of abstractly call Marquette Park–and I’m not just talking [about] neighborhoods. I’m talking [about all of the] many grassroots initiatives, environmental stewards, faith-based centers like IMAN ( the Inner City Muslim Action Network) and SWOP (the Southwest Organizing Project). I’m also running into artists at the park who are out and about, artists existing entirely outside of the contemporary art scene of the city that we three are very familiar with. It’s really beautiful. The openness and the diversity of the social domains that Marquette Park holds are the most special part for me, and that range and breath are informing my mode of operation for or this year.

As a curator, I am not looking for creative practitioners making works that look any particular kind of way. I’m not even looking into specific materials or even particular installation structures. Instead, I’m thinking of the medium of co-authorship or collaboration, social participation. I’m thinking of aesthetic collectivization. I’m thinking of these modalities because there’s just so much, right? And I feel like these are approaches for the kind of binding and connecting work that I’m doing through this Residency.

One example [of this] is “Destiny’s Give N’ Go,” [which is a project that will be part of my Anchor Curatorial Residency]. This installation is still very much being conceived collectively. Destiny’s Give N’ Go (DGNG) is a collaboration [between myself and] Deon Reed, who is a sound artist and designer, and also with SWOP. SWOP has a major presence on the Southwest side as a coalition of several nonprofits and collectives in the region working together. It’s not just this theorizing, it’s this collaborating and action.

CF: The running idea [for Destiny’s Give N’ Go] is to create a freestanding facade that is a bit fantastical but draws inspiration from the diversity of cultures and businesses that make up the cultural spectrum of 63rd Street is, [which is where the facade will live]. The installation will invite residents and local artists to respond to the prompt “What futures do you envision for public space?” by creating 2D works, graffiti prints, and other paperwork. These creations will be wheat-pasted onto a replica corner store facade installed in the park.

Sixty-third Street is permeated by many communities and religions; there are pockets that are the Latinx diaspora, Muslim Palestinian communities, Black communities, and also historically Lithuanian, Jewish, and Eastern Europeans. It’s a commercial strip of the Southwest side that I feel a lot of people are very proud of. However, this pride is not free from the shadows of historical redlining practices and other issues like extractive capitalism, predatory systemic practices, and racist disinvestment. DGNG particularly takes on the businesses on the strip that are there for the purposes of extraction by selling highly processed food and outsider businesses that make a lot of assumptions as to what the community needs– the kinds of businesses that fill the street and our imaginaries with signage advertising ”cigarettes”, and “alcohol.” Such businesses visually bombard you with products that they think you need, that are the most lucrative; the ultra-processed foods that have the longest shelf life. These businesses thrive in food deserts and are also part of the public imaginary of food deserts. The goal of DGNG is to commandeer this language of visual semiotics driving a toxic culture consumption. So the idea is to flip the tables and commandeer loud predatory marketing tactics towards an aesthetic collectivization that imagines new healthy futures for the residents of West Lawn and Chicago Lawn.

SH: Does DGNG sell products or not, the signage on the facade makes it look as if it does? I think it [should] sit right in front of the field house. As you touched on earlier, it’s a beautiful landscape where you have all the [right] elements: the sun, the water, the earth. So maybe it’s an exercise in manifesting.

It would be interesting for artists to create an object [for DGNG] with no boundaries. It could look like food, but be like a soft sculpture. It’s intriguing to me on many levels.

This also makes me think of these little assemblage boxes that I started putting together to tell family stories through cigar boxes. As you open [them] up, there might be an antique soap dish lined with sage and dried sunflowers or whatever. Vintage photographs sit in the lid. I am storytelling through found objects that are imbued with energy and their own history. That is the artwork. It’s called N’kisi (N-K-I-S-I) , [which is] a Congolese word for energy–it means to imbue an object with power.

My assemblage boxes are another way to connect with or channel my ancestors, you know, a slower way of working. My process is to meditate on these objects–what they are, who they may have belonged to, their form and function, and then give them a new purpose, which is what you’re doing with Destiny’s Give N’ Go. You are recontextualizing “corner” stores, mom-and-pop stores, hair and nail shops, etc. You’re giving new context to that which is familiar–making it unknown, and I find that to be really fascinating.

TJ: [Earlier we were] talking about cycles of stress, cycles of grief, and places of ease and rest. It sounds like one of your goals with this potential project, Carlos, is to put front and center one of the major, inhumane issues that are happening in our communities that have been normalized. You travel down 63rd area, where we have normalized these ads, unhealthy eating, and disinvestment. So it seems like [the project will be] enacting a [different] future, but also putting [the problem] front and center.

CF: I think part of it is a question of futurity. I think a lot of my work exists in a kind of an optimism, but I’m kind of messy in the sense that I’m commandeering. I’m commandeering structural power toward placemaking. I have a series of portable wheelbarrow structures that will be activated by three artists that would coincide with the Day of the Dead Festival at the Park, which is also tied to the Residency.

TJ: Recently reading “Who is Curating What, Why? Towards a More Critical Commoning Praxis”, John Kuo Wei Tchen reminds us that the root word for curate (cura) means ‘to care’. Curation is a form of public service work and curators are public caretakers. I love it! Tchen speaks about how, through this inter-institutionalization of curation, the care within the work began to focus more on the objects, more on archiving, and more on building yourself.

Saidiya Hartman asks us, “How long are we going to be married and dedicated to these colonial stories that have been told about our lives? When do we disrupt not only these archives but also the stories of what my existence means?” And so when I think about curation when I think about art–especially when the root word means care, means healing–I wonder how we are going to dissect our practices, especially with where the world is right now. How can we recharge the meaning? How am I using curation as a liberatory tool, a radical tool to push the narrative? Our practice has been so institutionalized and removed that the ways that we are told to perform this practice, to show up in exhibitions, take out the emotion. It removes real communal connection. Even when we’re like, this project was inspired by the Black radical practices, I’m like, are you sure?

CF: Yeah. It’s lost its root meaning, which means to tend to, to care for. Tiffany, what blows my mind is that in Spanish, more the direct translation, at least Mexican Spanish, is the word curador, which means healer. Then curador as a contemporary curator quite literally means someone who works with herbs or who heals with the earth. So when I tell my family what I do they’re like, “Wow, you work with the plants?” (laughs)

It’s really fascinating. It reaffirms and reassures me of what I’m trying to achieve in my work and also what I see of my peers who are doing this. This is really, truly radical practice, whether they know it or not.

Artists and curators are energy dealers almost.

SH: Yeah, I love that. I learned service through my brother’s illness. I knew I had to be that steady, stable person in his life so that he could always have a soft landing, and in the same way, I serve many vulnerable communities. If everyone understood that we are carers of the planet, land, people, animals and every structure out there–and that everything starts with care, we would be living in an entirely different world.

TJ: Sonja, do you have anything else for us that you want to touch on before we close out?

SH: I’m gonna say, Carlos don’t forget about who you are in this whole curatorial process because your vision and voice are uniquely important. You are already serving the community and doing the care work, you know what I mean? You are already in alignment and very connected to artists, people and community.

Don’t forget about your own personal vision and aspirations. I feel like I just wanna give you [both] permission to explore your brilliant expressions of placemaking and built environments through the Anchor Curatorial [Residency] and more.

About the author: Carlos Flores is an installation artist, radical community arts organizer, curator, and flower farmer. Both his visual practice and organizing work center around creating space for connection, generation, and care to take place. As programs manager at the Chicago Art Department, he leads the organization’s residencies and exhibitions, supporting twenty civically minded artists and over 100 free exhibitions and programs every year. Carlos is also the founder of Contra Corriente, an annual festival highlighting the work of artists, activists, and organizations working to advance racial and environmental justice on the South West Side of Chicago and beyond. (Photo by: Miguel Vasquez | Instagram: @miguelphoto1)

About the author: Tiffany M. Johnson is interested in spaces (and a world) where Black people can exhale. She is a researcher, survivor (advocate), and curator passionate about community building through imaginative, underground, and cooperative practices. She attended SOAS, University of London, for her Master’s in Migration and Diasporas Studies. Her studies continue through her DIY Ph.D., a long-term art and hood scholarship project on alternative ways of being within spaces combating oppressive structures. Through a radical afrodiasporic feminist lens, she is interested in rebuilding human-to-land relations and centering understudied subjects and community care systems. Tiffany is a 2022-24 Threewalls RaD Lab+Outside the Walls fellow and co-stewarding the development of the survivor support mutual aid group, Project Nebula.

About the photographer: Prince Jai is a multidisciplinary artist currently practicing in Chicago, IL. His practice has transitioned over the years and has included ink drawings, photography, cinematography, acrylic painting, fashion design, woodworking, interior design and more… Each installation is an amalgamation of experiences, ideas, and disciplines. A desperate attempt to explain my emotions, feelings, and thoughts in a way that puts the audience in my head or near my heart by any means necessary. An approach that was formerly referred to as experimental would now better be categorized as experiential.