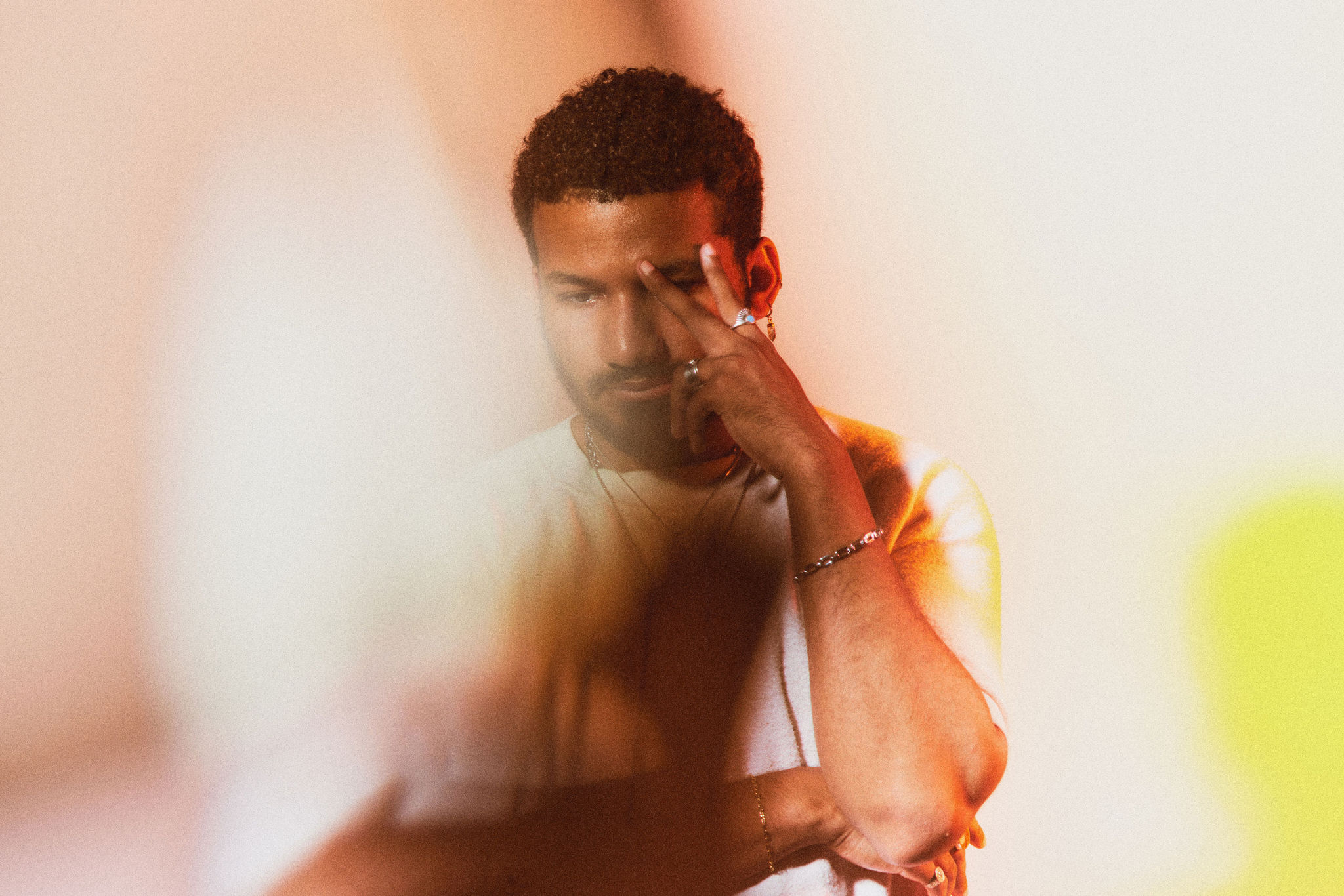

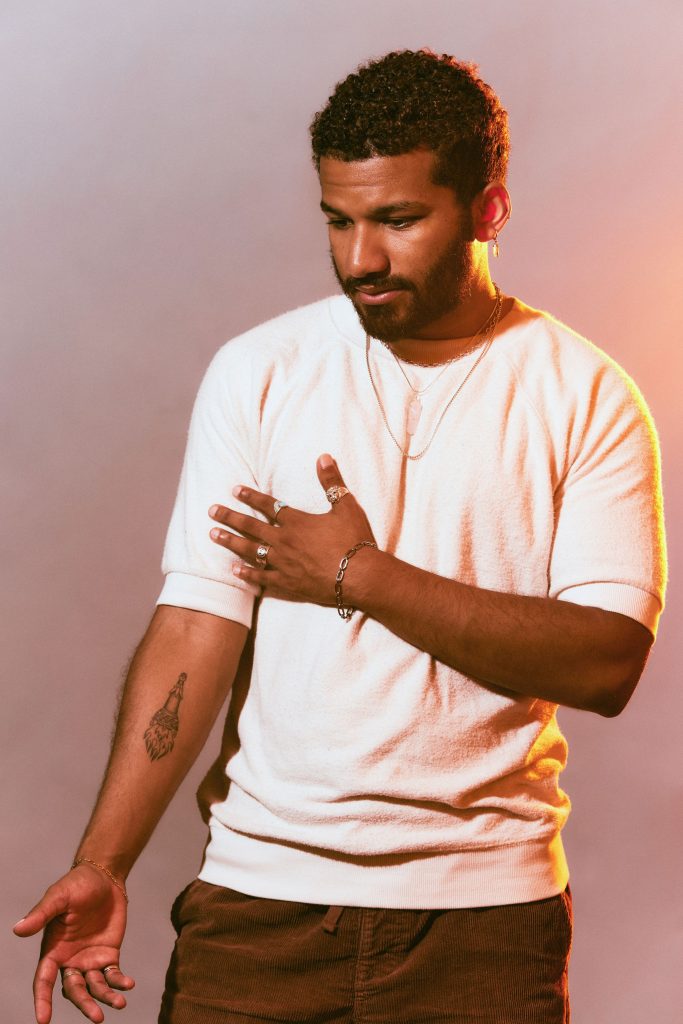

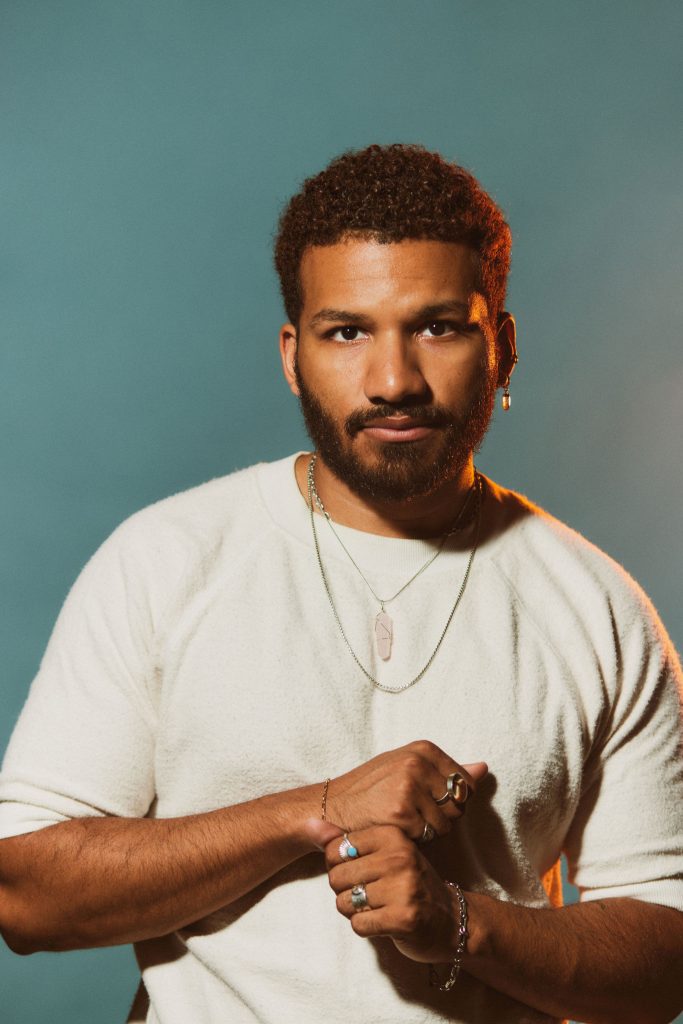

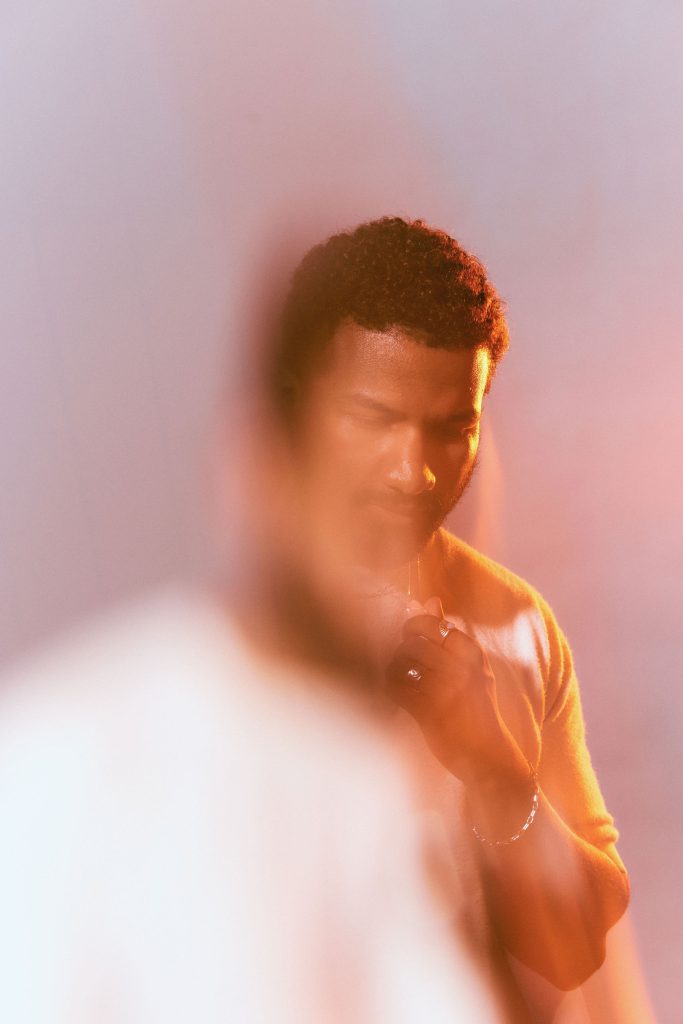

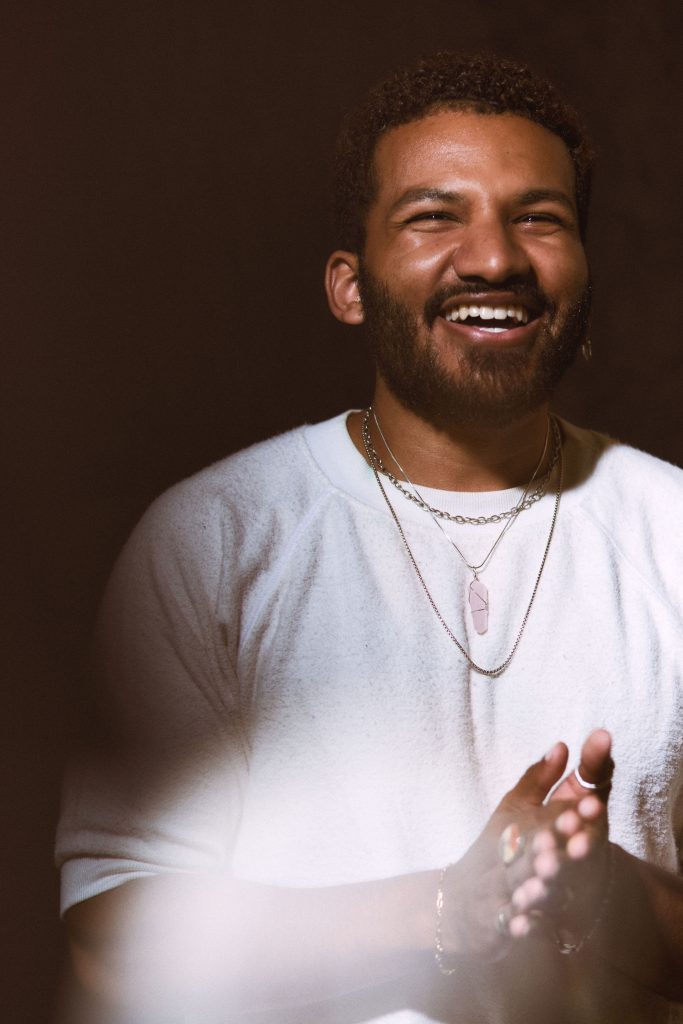

The two-minute walk from my car to sarah joyce’s studio in Humboldt Park feels like I am trudging through water. When I see Rich Robbins, he greets me and the humidity with open arms full of gratitude and warmth—that’s Mr. Soft and Tender for you.

As sarah sets up her photography equipment, I grab a lime Polar Seltzer from her mini fridge. “These are from my hometown, Worcester, Massachusetts!” I excitedly tell Rich. As we talk about our hometowns, we inevitably bring up sports. Between us former East Coasters, Rich, a Philly fan, and me, a Boston fan, there’s room for a whole lot of ego. However, I feel no trace of that with him. Even as I recount the NBA Eastern Conference Finals back in May, Rich shares the thrill in my animated retelling of Game 6 when Boston Celtics’s Derrick White’s buzzer beater pulled the team into victory. But perhaps more meaningful to me, he shares my heartbreak as I talk about their gut-wrenching defeat to the Miami Heat in Game 7 after a hard fought playoff season. Months after the loss, he treats my disappointment with thoughtful care.

Rich Robbins, a man whose talent and passion is distinctly clear in his genre-bending music, prioritizes community in all his endeavors. From writing and producing music, organizing community talks and his open mic, and his role as an educator, he rightfully claims his autonomy in this world while holding the door open for anyone who is willing to take a leap of faith on themselves to claim their space.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Shivani Kumar: You’ve got roots in Philly, you attended college and made music in Madison, Wisconsin, and now you’re back in Chicago. What does it mean to you to be a Chicago-based artist?

Rich Robbins: I don’t feel like I have the same claim that some artists do in Chicago. I’ve been here now for seven years. This is the longest I’ve ever lived anywhere. Being able to kind of claim Chicago as a home is important for me because I didn’t have that ever growing up. For a long time, [people joked], “Oh, where are you from in Chicago? Oak Park? That’s not Chicago!” I don’t know what happened, but Oak Park got [its] clout up and now people recognize, “Oh, yeah. That’s like the same shit.”

But I’ve also poured myself into the city so much, and it’s really reciprocated that love. Chicago [has also been] a Mecca for hip hop for 15 years or so. It’s beautiful to come off with such a rich history. Even a rich recent history of Chance [the Rapper] and Saba and noname and Mick Jenkins. They are all my peers age-wise, but I look up to them so much career-wise. There’s a lot that they did in their younger years I still to this day try to emulate because that’s the core of Chicago to me—community-based music. I wouldn’t wanna do this any other place. At this point, I could go anywhere I want to go. I think the music would be very applicable in other cities. But there’s something about how Chicago really prioritizes [its] community and network that I stay with.

SK: Chicago almost feels like a playground with how many possibilities there are in the creative scene. Like you said, it’s overflowing with talent. I see how you approach and expand this environment with genuine love and appreciation for your craft and your peers. You’ve collaborated with Saba, Mick Jenkins, and Shawnee Dez. Most recently, you released MRK with StevKob Studios, Master Steve, Alexa Willow, and Amber Reverie. How do you see these professional and personal relationships contributing to Chicago’s music scene?

RR: Chicago is different from other major cities in that we don’t have any major record labels. The only way we can really get music out is if we help each other get music out. When I worked with Saba and Mick, they weren’t as [successful] as they are now, but they were on their way up. I was in Madison [at the time]. I wasn’t even in Chicago. So I leveraged my YCA [Young Chicago Authors] connection that we had and introduced myself to them. It was this “we’re all in this together” mindset that helped elevate those collaborations, you know? The song with Mick and the song with Saba are some of my most successful songs. Collaboration for me has resulted in the most success. This city doesn’t work unless you are willing to collaborate with each other. Even working with Master Steve, Kobe [Critchley], Alexa, and Amber—a majority of those people on that song are not from Chicago. But I think there’s something that happens to you when you come here that you understand, “Oh, I gotta collab with people”.

SK: That is so true. I feel that way, too.

RR: In any major city, you’re gonna get a lot of different personalities, right? You’re gonna get some people that love to collaborate. You’re gonna get some people that say, “I don’t know you. You’re not a part of my clique.” But I think the clique-y side of things is more suppressed here and more open mindedness is welcome here.

SK: I love that. I feel as a poet, I have had that experience [where] more people are willing to read my work, come to open mics, [and] support me.

RR: Yeah, I think the open mic—that’s a good example. The open mic network here is so strong because the open mics support each other which is so cool. I never knew that until we started Respect the Mic. It’s like a video game. I feel like I uncovered this new part of the map where all of these other organizations started revealing themselves and wanted to collaborate with us. And we were a little baby open mic. We didn’t have anything. And now, you know, we are where we’re at now. I definitely hear you on that.

SK: So you were just talking a bit about success—Saba’s success, Mick Jenkins success. It’s clear that you embrace the talent in the music scene and don’t fall into this scarcity mindset of there’s only room for one of us to make it big. What is your definition of success? What does that come down to for you?

RR: Success is a respected legacy for me. Obviously, we have a finite amount of time. The only way to extend that—growing up I was really into superheroes, and I still am. Fantasy things. I think a big part of what comes with those storylines is the idea of eternity and embracing eternity. But we don’t have eternity as flesh and bone. [We] have memories and, in my world, music. That’s why I’m so selective with the things that I’ve released, because this is a part of the legacy when it goes out. I’m kind of envious of artists that release and release and release. I just can’t do that.

SK: You’re very intentional.

RR: Yeah, that would be reckless with the power we’ve been given. That’s why I approach each song in similar ways I used to approach poems. It’s a craft. It’s something that needs to be molded, cared for and compassion needs to be poured into it every step of the way from the writing process to the recordings to the production to the engineering to how we perform it on stage to who we perform with on stage. Every iteration of the song becomes a part of the legacy. What success looks like to me is people reflecting on the legacy and being able to learn from it and find joy in the legacy.

And I’d be lying if financial shit wasn’t a part of that. [laughs] I want to be able to feed an entire family off of this work. I don’t think that was always the case. I think early on it was for fun, and then it got to a point where I said, “Oh, we could do this for a lifetime.” Now [I want to learn] the business side of things, all the boring stuff, the things you hire someone else to do, so that when I do hire someone, I know how to do what [they] do so [they] definitely gotta do it right. Success is legacy and, even though it isn’t as much, financial success is involved in that, too.

SK: You were talking a bit about your approach earlier. You wear so many hats—you’re a rapper, songwriter, producer, and educator just to name a few. When you work on a new music project, what is your approach?

RR: Each song I have released has had a different process. It’s ironic, right? My job is to break down the process step by step for folks at YCA [Young Chicago Authors] and even before as the spoken word educator at OPRF [Oak Park and River Forest High School]. My job was to breakdown poetry and make it accessible for students who never wrote a poem in their life. But I don’t break down like that for my own process. It’s so organic. I’ll give you an example. Lately, I pick a beat off of Youtube. Then I start to write. Once I slow down, I pick a different beat and use the same verse. I transfer the writing over and start to write to that. And it injects a different energy into it. And then when I get to a point where I feel comfortable with this verse, then I produce around the lyrics. Then we have an original song. The energy is always shifting, and it’s dope, and the writing is good. The process for me is fluidity. And fluidity is always shifting. I think it’s just keeping an open mind. I don’t have to be stuck. I don’t have to say, “This is my process so I have to stick with this.” The process is open mindedness.

SK: I love that you say that. It feels like you give yourself a lot of grace to evolve not just from era to era of your music. But you’ve taken it even more micro—project to project and song to song it does not have to be the same for it to still be good art. There’s, of course, no calculation.

RR: Yeah, I mean I’ll take it a step further. Verse to verse—the energy shifts even within a verse. I love exploring. I’ve been having a great time the last year, maybe two years, becoming a stronger vocalist and singer. I’m nowhere near where I wanna be yet, but that blended in with the ability to write raps has been a lot of fun to explore. Maybe half of the verse I’m on some melodic stuff, and then the next half I’m gonna spit a well-crafted verse, you know? We shift that energy even verse to verse.

RR: Wow, thank you for saying that. First of all, that’s every musician’s dream compliment right there. I think it’s setting intentions before the show. If I go up there and say I have an intention to have a great night tonight, and then I proceed to be terrible, then I’m not hitting my own intention. So it helps keep me accountable, and I think that people see that then. I told the crowd, “I’m about to be ugly as hell up here so y’all feel free to be ugly, too.” Not that nobody needs my permission to enjoy themselves, but I think it’s like this permission to just let go, you know?

In college one of the things that one of my mentors taught us was to leave your ego at the door. I don’t want my shows to be a place of ego at all. That is the one spot that I can like completely be myself, and it’s like either be yourself or drown. And I don’t want to drown. I got 45 minutes—let’s go. Let’s do it. Let’s pour everything.

SK: Everyone can feel that you are genuinely sharing your intentions. Intentions can be such a personal thing. They can be something you say to yourself in the mirror, repeat them to yourself before bed, or quite literally they are your prayers. There’s a lot of bravery and vulnerability in sharing that with your audience. Those things are such a big part of “Soft and Tender,” but to see you live it out is really incredible and part of why people connect to your music so much. I left that last show, Dear Chicago at the Golden Dagger, thinking, “This is why I moved to Chicago.” To feel safe, to have fun, to experience joy is really unmatched especially in a world that feels very difficult right now. It just isn’t lost on me that’s only possible because of the community that you’ve cultivated. Tell me, what does community mean to you?

RR: Community is everything. I come from a big but very close family. When I was younger, I used to think that both sides of my family were related. [laughs] And like one side is Black and one side is Mexican. They’re clearly not related, but I just had this concept in my head that like everybody loves everybody. Then, obviously, as I get older, [I got] a little bit more jaded. It doesn’t make sense to me why people would hate other people. Why would you do that? We don’t have time to do that, you know? We don’t have time to be mad at each other. We don’t have time to bring each other down. If we just focus all of it on building, we could do so much.

I recognize that I cannot do much alone. I don’t mean this in a self deprecating way. I’m not the best writer, best singer, or best performer as an individual. I think I’m really good at it, and I think I do my thing. I think I can hold a stage by myself, for sure. But if I’m bringing that power level by myself, imagine what that looks like with so many other people with me. From whoever is doing merch to whoever is doing photography that day to the vocalists to the sax player to the flute player to the DJ to everybody that has spent their hard earned money to come and support you. We all make this machine go. It’s like a body. When you hurt one little part of your body, the rest suffers. And what better metaphor is there to understand that we all need to be diligent about supporting one another. If somebody or something is not healthy, I think the community has to come together to either invite that person in and invite their healing in. Or decide collectively that we need to move on from that type of energy because, again, we don’t have time to be not building upwards.

SK: Definitely, I mean it’s a world building kind of energy.

RR: Absolutely.

SK: It’s been a little over a year since the Soft and Tender series had its premiere as a private screening. And it’s been about six months since your Soft and Tender EP was released. These projects center vulnerability as a Black man within the father-son relationship. Where did your relationship with that project start and how has it evolved since?

RR: It started like the first week I moved into my condo. I wrote the song “Soft and Tender” in my living room, and I had the beat on loop. And this is a new living space, right? So I was blasting music. I was having a great time. A couple days later, I got a noise complaint about how I’m playing music on repeat. [laughs] “My bad.” But the song, “Soft and Tender,” was written that first week.

SK: That’s a great way to christen the space—a noise complaint for “Soft and Tender” out of all songs.

RR: Right, it ain’t even like a loud, in-your-face kind of song. But my neighbors are grumpy, whatever. [laughs] I remember my roommate of the time coming into the room and saying, “Yo, you got something with this.” It was a new thing for me to talk about my dad in that way, to talk about my family in that way, and to talk about myself in that way. I’ve always been interested in exploring masculinity in my work, but I think there was something that we just really hit—like a little window with that one. So it started there, and then a friend of mine, Link Kabadyundi, who is from Toronto was visiting. He heard the song and said, “You know, this would be cool if it was like a series or something.” Then we started expanding on what that would be.

I really love the interview series like LeBron [James’s] “The Shop”and Jada [Pinkett Smith’s] “Red Table Talk”. I thought it’d be cool if I sat down with other Black men and talked about fatherhood through the “Soft and Tender” lens. So we crowdfunded a couple thousand dollars to make three episodes and recruited the men that were going to be a part of it. Then it blossomed from there into this brand—this event brand. We started throwing parties under the “Soft and Tender” name, hosting live conversations, and we [made] this beautiful film series that we’re looking to distribute and fund. Then it evolved into the EP. It all started from that one little song. Just like you said—world building. I love that idea of building an entire universe around something, and ironically, it’s one of the shorter projects I’ve ever released. But I think it’s one of the most true to myself that I’ve ever released, and I know that because of how effortless we can perform it. I don’t feel like I’m performing. This is just normally how I talk.

SK: Yeah, you’re speaking your truth. So many people connect with it because—obviously, we have very different identities. But there’s so much in “Soft and Tender” [about] familial relationships [and] just figuring out how to coexist with each other. I listened to it recently, and I had just had a little disagreement with my dad who lives all the way in Massachusetts. And I’m over here in Chicago. I took a second away from the disagreement and realized it’s not that deep. It’s never that deep. There’s not enough time to stay angry, especially with people you love. There’s room for boundaries and respect, but there’s no room for grudges. That’s such a beautiful part of the song—that there’s so much room for grace and forgiveness within it.

RR: Yeah, that’s what’s up. Because that’s what my dad taught me. I’ve seen him mess up several times, and it’s the way that he bounces back from that. I’m always impressed with the gentleness in which he bounces back. He doesn’t have to. He’s a strong guy, and so he could be a brute about things. I see men do that. I see men lean on their physical strength in order to get through the walls that block them. I think it’s just so much stronger to watch my dad say, “I’m sorry”. There’s so much power in watching a Black man from Philly say, “I messed up, and I’m sorry.”

SK: I bet it helps you say you’re sorry.

RR: Hell yeah. Hell yeah—cause the strongest person in my life showed me how to do it. It’s not easy all this time, but I think it’s accessible for me because I watched him do it. I’m glad that translates to the music.

SK: It definitely does. So “Soft and Tender”—it’s clearly more than a song, more than an EP. It’s this whole vision, this whole world. So much so, like you said, you’ve thrown two “After Hours” parties with your manager, Felton Kizer. What was the inspiration behind those events for the two of you?

RR: When we looked at “Soft and Tender” as a whole, I [asked], “Well what’s missing here?” We have our soft moments. We’ve got our conversations. And we’ve got the music. But we also like to party. And we like to network with people. And we’re also good hosts. So why don’t we just invite people to come party. We’ll book some great DJs and people will do their thing. The first one was a lot more dance heavy. The second one was a lot more conversation and network heavy. We’re still finding our stride with it, but I love the idea of trying to find different ways of inviting people’s vulnerability. How many spaces can we put that in? That’s where we’re at. That’s what inspired After Hours. We didn’t have a party space, and there’s also nobody throwing a party like this. So we did it.

SK: I was telling you earlier, I’m a morning person and don’t stay out late too often. But I saw the party, and I [decided], “I gotta go,” especially because you promoted this party by encouraging people to take care of themselves and take care of each other. That is a clear through line in all of your work—your shows, your songwriting workshop you lead at the YCA, your open mic—Respect the Mic, and at these After Hours parties. It was comforting to know I can go to this party that’s definitely still a party, but I don’t have to drink if I don’t want to. I don’t have to dance if I don’t want to. I could come as I am, and that’s enough. It’s such a beautiful space you fostered, that people can just be enough as yourself.

RR: That’s crazy, you’re making me realize something. I didn’t have much autonomy as a kid. Or confidence. I didn’t know that I was allowed to take ownership of my life. Some of that came from how I was raised. I was raised in a church, so being modest was a big thing. As I got older, claiming my own confidence was hard. I was always very shy in school. When I was in high school, I lost a family member going into freshman year. That really messed me up. My participation in school decreased, and I was already naturally very nervous. It wasn’t until [I discovered] spoken word my sophomore year of high school that I began to claim my story and perform it in front of people. And how invigorating that was—[to realize], “Oh, y’all are gonna listen when I say something?” I never really had that before. Providing spaces for other people to have those realizations [and feel empowered] is beautiful to me. It took me a long time to find that. If we can facilitate those spaces, then cool.

SK: As an artist who promotes their work and cultivates community on social media, how do you create boundaries for yourself? [How do you balance] sharing things with your fan base but also keeping some things sacred to yourself?

RR: That’s a really good question. For a while, I was oversharing on social media. I sometimes go back to my old archived photos and see the captions. I think “Bro, why? [laughs] What were you saying, man? Why are you even giving this information out?” Now I think it’s all about being concise for me. I don’t really post on social media unless I have something to say. And I just leave it at that. It’s a struggle though, for sure. I’m definitely on my phone way too much sometimes. There are times when I’m itching to post something because it seems like everybody is posting something, but I’ve got nothing to post. Will people forget about me? So I don’t quite know how to slay that dragon yet. It’s a work in progress for sure. I’ve been challenging myself to be outside more, network more, and not be scared to introduce myself to somebody I don’t know. The more I do that, the more I have things to post. Now I just post when I’m at a location and pan around and show people we outside with it. But personal things like [my] love life and [my] cat are just for me.

SK: Yeah, you deserve things for yourself. Alright so, Respect the Mic is an open mic you started before the pandemic. It has restarted back in May since 2021. How has it grown and evolved?

RR: The name Respect the Mic comes from my mentor, Peter Kahn. That was a term that he used all the time. He instilled [it] in us from a young age, If somebody has the microphone, they should be the only one talking and everybody else should be paying attention. So I thought that was the perfect name for the open mic. A couple months before September 2018, I stumbled upon Positive Space Studios—shout out to my cousin, Sydney, who took me there. One of her friends was showing her art at that gallery. For some time I had been looking for a place to perform and thought this would be a dope space. I talked to Melissa Polonsky, who owns Positive Space with her husband Jordan Polonsky. I pitched her this barely thought out idea for an open mic, and she [agreed.]

So we hosted our first open mic. It was just supposed to be a space that my homies could come, perform, and practice their work. That was a space that I felt like me and my friends were missing. This low pressure [space] is for trying things out because we have so many spaces where we gotta be perfect or otherwise people check out. Every month more and more people started finding out about it. There were some months in the beginning where it was rough. We had very low attendance. I had to shift my expectations about it. But then something happened. When COVID hit, we did some virtual ones, but that was just a lot [of work.] But a lot of people kept asking me when we were gonna come back. I didn’t even know y’all wanted this. Jess, formerly Chandrikah, hit me up and said, “You gotta bring Respect the Mic back.” I said to her, “Help me bring it back”. I want a team if we bring it back. So DJ Napp signed up to be on as our resident DJ. We have some rotating photographers, Colleen Mayer, Carlo Liou, and Jay (Jose Castillo), and a videographer, Rachel Bekele. When we came back we had about 80 people come in a 40 person capacity space. All the things I used to worry about, I don’t worry about anymore. I don’t have to worry about attendance. People are gonna come now.

SK: The one I went to in May, there was an open mic sign up sheet where some people weren’t able to get onto the list. There was that much interest! Hottest club in Chicago!

RR: Hottest club in Chicago, man! Hottest open mic in Chicago! Also, the most intimate open mic in Chicago. It’s become a familial kind of thing. People put it on their calendars. They look forward to seeing their friends and peers that they’ve started networking with. I know people who have met at Respect the Mic that are still working together to this day. They met in 2018 and are still collaborators today. I love seeing their work. It’s so beautiful. It is one of my favorite things that I’m a part of, that I do. If anybody is out there reading this, come to Respect the Mic every last Thursday of the month at Positive Space Studios [at] 3520 W Fullerton. I do reiterate, shout out Melissa and Jordan. They’ve opened up their doors so generously and graciously embraced the community like it’s their own. In a lot of ways, it is their own because it’s their space. Yeah, Respect the Mic. That’s where we are at.

SK: Last question. Bringing it back to you. What are your hopes for your music and palace within Chicago’s music community?

RR: I would love for my music to be like one of the pillars—like Chance is. Even like Lil Dirk is. I don’t occupy that space. But I want the name, brand, music, and quality of the music to be an example. Like when we talked about legacy—I just want people to hear a Rich Robbins song and say, “Oh, don’t skip this.” Or get that feeling where they feel Respect the Mic or they feel the “Soft and Tender” series when they listen to the music. I think so much of the music we listen to is associated with other things beyond the music. I was just watching an interview with Drake actually and he [said], “I understand when people say I want the old Drake. Well, what do you really want? Do you want nostalgia or that memory of listening to one of my old songs? I can’t give you that. But what I can give you is quality music everytime I drop.” I want people to build memories around the work we put out and the music I put out so that everytime it comes on they think, “Yeah, this brings me to a place of joy.”

SK: You’ve already done this. And you’re gonna keep building it.

RR: Yeah, you gotta keep doing it! And if somebody out there has a lot of money that [would] allow me to keep doing that and providing that, I would love that. I want to keep it going for as long as we can. I don’t see why we can’t keep it going forever.

SK: My last thing—do you want to plug any performances or upcoming events?

RR: Respect the Mic’s five-year anniversary is August 31st. And beyond that, every last Thursday of the month you can come to Respect the Mic—we will be there. And also any youth out there, we’ve got Every Word Counts, the songwriting workshop I facilitate at Young Chicago Authors every Saturday starting September 16th. It’s a great way to experience music and learn how to make it yourself. I’m also headlining the Taste of Chicago this year on Saturday September 9th. That will probably be the biggest show of my entire career. That’s gonna be an important moment and experience. I also am really excited about a couple songs that are coming out that will expand on this legacy that we are building up. I want people to get excited about that. I want it to be a moment. I want people to stop what they are doing when I drop it and think “Oh, I want to listen to what he’s got to say.”

About the author: Shivani Kumar is a poet from Worcester, Massachusetts. Her work is guided by her passion of connection to destinations, opportunities, and self. Her poems pull a reader into a world where they can find themselves arriving to emotions and memories that are limitless and can nurture healing in a world that often does not create the necessary time and space for such renewal. She is currently working on her first poetry book that holds themes of community, belonging, grief, and identity as a Tamil-American woman. Her work can be found in Vagabond City Lit, Chicago’s South Side Weekly’s The Exchange column, Sixty Inches from Center, and forthcoming in Sarka Publishing. She resides in Chicago, Illinois where you can find her attending poetry open mics, buying yet again another book, or exploring the breathtaking lake front.

About the photographer: Sarah Joyce is a photographer based in Chicago. In addition to portraiture, she’s been documenting the cultures, subcultures, and countercultures of Chicago for the last 10 years as a co-founder of GlitterGuts. Photo by Mariah Karson.