This essay is the finale of Paloma’s three-part essay series. Part one is “Con Mucho Amor, Mi Plátano.” Part two is “Pa’lante.” These essays can be read in any order or as stand-alones.

Flowers appear on the earth; the season of singing has come, the cooing of doves is heard in our land.

Song of Songs 2:12

Doves grieve the death of their mates watching over and attempting to care for their bodies and later returning to the place where they died. Maybe that’s the origin of the term mourning doves. With Larimar, I kept returning to the failed relationship, and the part of me that I became with them died. My mind would wander and encircle; how they looked when they danced, their insatiable smile, and the beautiful way that they made art. The same way seeds die for a bud to bloom. My unrequited love had to die, but I didn’t want to keep returning to that grave. In the Black tradition, death is a celebration. We call it homegoing because it’s a return back to the divine whence it came. Dancing, hysterics, laughs, and a meal that is a balm for all troubles. With that reverence, sadness, and glee, I come to terms with losing the romantic relationship and friendship with Larimar.

While leading a writing workshop, I told my students that my partner nicknamed me “Paloma” because my name means dove in another language. A student chuckled. “What’s so funny?” I asked during our icebreaker. He explained, “Paloma is a Dominican slang word for naive.” I wondered if Larimar was aware of this double entendre since they are Dominican. They had a few years on me and would constantly mention how youth made me see the relationship with wonderment. They’d say, “Sometimes I think you like the idea of me, but do you like me?” Perhaps they were calling me naive in a passive way. They said it so often that it became harder to justify myself and my feelings.

I purged all the items that reminded me of us: the blue bodycon dress and the shorts they said cutely showed my booty, earrings with their logo of snakes coiled around plátanos, and a clip I used for my opened chips because they always had the random tool I needed and didn’t have at home. Sentimentality to objects is a powerful drug, almost as powerful as love itself. A glimpse of an ensouled object would make me replay arguments in my head, cry, or even remember slow dancing in their apartment to Sade. I couldn’t let myself be a junkie for these objects and moments, fiending for the past or what might have been. This was part of my detox in addition to journaling, therapy, and allowing myself to feel all the highs and lows.

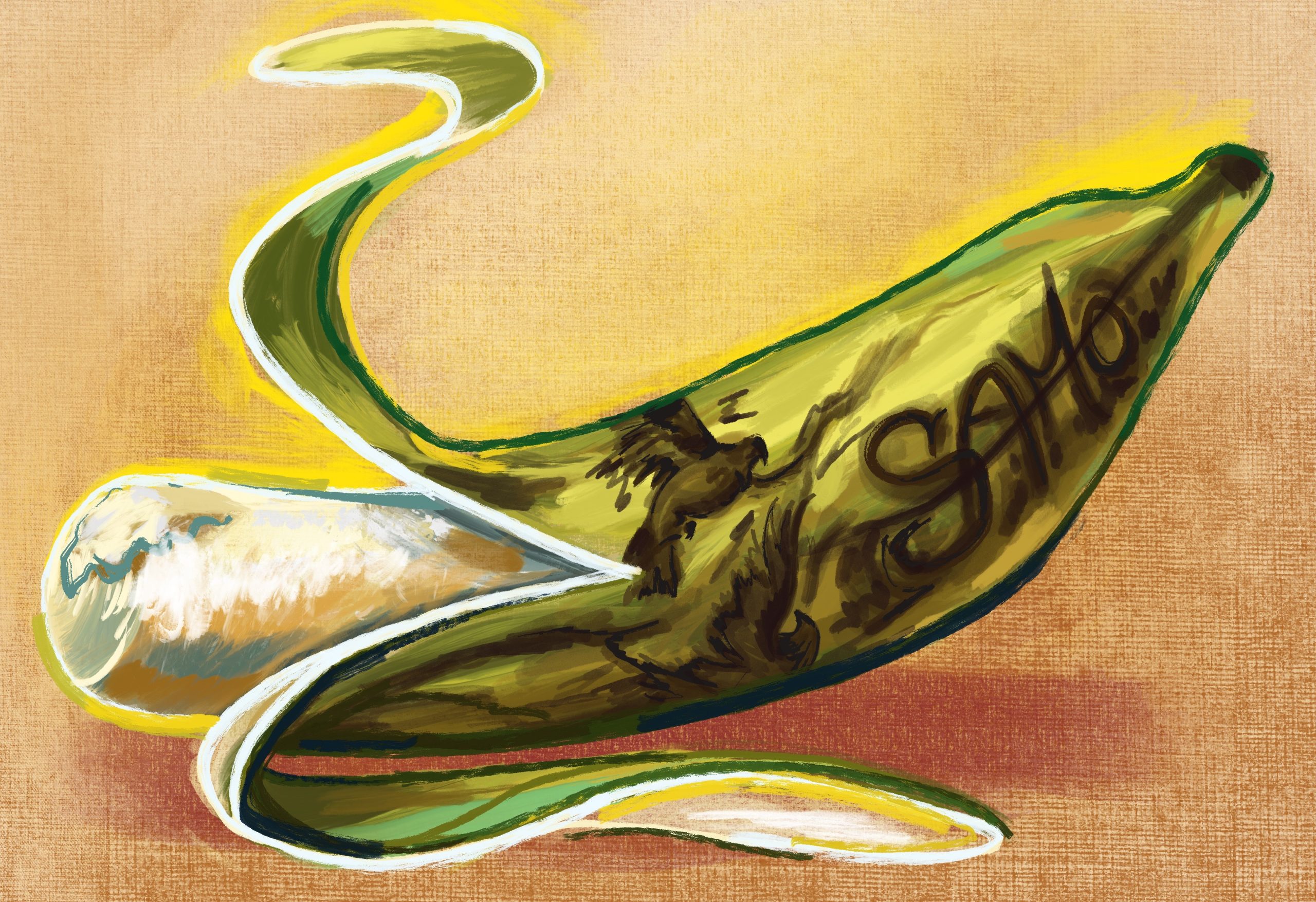

The turbulent relationship made me think of the complicated life of street artist and painter Jean-Michel Basquiat ridden with romance, mystery, and struggle. Legend goes that when Basquiat and Al Diaz smoked a jay, they came up with what became a famous graffiti tag SAMO as teens, an abridged version of “same old shit” or some critics believe that it was a religion the pair came up with. It was about the trappings of capitalism. This became their tag and an immortalized annotation with a strikethrough within Basquiat’s paintings. It’s both a marker and an etching out. Thirty-five years after his death, I grapple with why he decided to cross out this term and include what he conceived as a teen well into adulthood. He could’ve painted over it and completely obscured the term, but he didn’t. Part of him must’ve wanted us to see it. But why? Perhaps, it was a reminder to himself of where he came from, an inside joke, a safe word, a cryptic message that only makes the people part of the if-you-know-you-knows lean in.

I wrote SAMO on a vision board I made in 2021. The phrase resonated with me. Post-pandemic obliterated normalcy. SAMO comes back to me two years later as I contemplate morality and the death of a relationship because, like an etched-out term, it becomes a part of me, but goes dormant. The feelings of love and passion must be blotted out so that I can fully move on and live in the present.

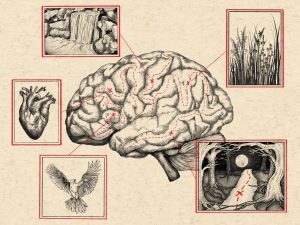

Along with the death of the relationship, I’d have episodic dreams where I would wake up drenched in sweat. In one dream, I hopped in an Uber on a sunny day. I don’t remember where I was headed, but I sat in the car unbothered. All of a sudden, the sky turned from blue into gray, commencing in a torrential downpour. It became harder and harder for the driver to see as the rain obscured his view. We started swerving until we were upside-down in a body of water. I clawed out the seatbelt and started kicking the window, as water poured in. I was too late. I woke up in a pool of sweat, presumably the water that my brain turned into a threat drowning me.

A friend of mine, a curandera and artist, told me about the power of the body to undrown itself: typically, done through crying. I began to detox my mind and body, but kept a marker of what once was so that when I found romántico, it would never be the same. I learned from that relationship that I want a dog someday; the friends of your lover are not your friends; to trust my intuition that when my spirit is unsettled about something, listen to it; and respect my boundaries and the boundaries of others. I also cherished reaching a new height in my hobbies and admiring talented friends, love among family, and most importantly, amándome. So here it goes: the remnants of what once was, all at once look casket sharp, and I finally put it to rest and am grateful for living a full life.

About the author: Paloma, a messenger bird, ‘cries for the people’ and captures the feeling of trying to grasp reality somewhere between nonfiction and fiction which redefines peace as settling the factions within yourself. They are a writer based in Turtle Island.

About the illustrator: Julia O’Brien was born and raised in Colorado before earning her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her work explores how the body can hold histories and tell stories as the boundary between internal and external identity. She describes herself as an image maker and a storyteller who loves learning new skills and hearing silenced voices.