Inside the Just Art Program at Cook County Jail: Part 2

Continuing the Envisioning Justice project’s coverage of Just Art, I sat down with Aimee Krall-Lanoue, a teaching artist who has facilitated weekly writing classes at Cook County Jail since May. Just…

Continuing the Envisioning Justice project’s coverage of Just Art, I sat down with Aimee Krall-Lanoue, a teaching artist who has facilitated weekly writing classes at Cook County Jail since May. Just Art, which began in 2015, currently consists of three teaching artists who instruct on visual art and writing. Krall-Lanoue is also an English professor and writing center director at Concordia University, and specializes in basic writing. She is interested in the ways that language is used to construct hierarchies, and increasing political awareness around language. One of her larger life goals is to create community writing centers all over the city, staffed by (paid!) writers who live in those communities. Over coffee, we discussed Just Art, pedagogy, and the structural barriers that prevent people from coming to writing.

Jordan Sarti: Can you talk a little about pedagogy and how you teach classes differently at a basic writing class at Concordia versus at the jail?

Aimee Krall-Lanoue: This is one of the things that I was very concerned about, was that I can make a lot of assumptions about my college students that come in. How they got there, what are their goals, do they have some competencies, some practices that they’ve developed. But it really also became about, there’s this structure of a college class. Which is: you come to class, you’re assigned writing, you do writing, I give you feedback on it, you revise it, you get a grade and move on. I get new students.

And all of that is wide open now because at the jail, these are men who are voluntarily taking a class. They don’t get any credit for it. There’s no reward system in play, there’s no built-in incentive in the way that there is, even if I have many students who don’t come to class or don’t do the writing or whatever, there’s still this implied structure for how things work and all of that is blown wide open at the jail. That I found hard to figure out: how do I make assumptions about these students? How do I make assumptions about why they’re there, what they want to do? What they can do? I really worked myself into moments of being really anxious and worried almost to the point of, oh my gosh, I don’t know how to teach reading. What if I have to teach reading?

But then once I started going into it, it opened up all these barriers that we place on what writing is, and how we write, what we do when we write, and who should write. And it’s really about trial and error. I bring something into the jail, and we toss it out and see what happens, right? But there’s so many material restraints: if I bring in something that we’re gonna read in class it has to be short. It has to be something I can print up. I can’t staple it together. I can’t have paperclips. So there’s all these sorts of challenges, right?

At the first class that I worked in, which was in Division XI, I believe, we didn’t have a table. We had chairs. We had no table, no desks, nothing to write on. How are they supposed to write when they can’t write on anything? That class fell apart, and it fell apart in part because they didn’t have the material conditions to allow them to do this kind of thing. Now in this other class in Division X we have desks, I can bring them pens, and we work with pens in class that I have to collect back.

We’ve gotten into a rhythm where I bring writing and we read it out loud and we talk about it and they have journal prompts that I give them. Originally, I gave them a set of journal prompts every week, which was also very hard, because the kind of journal prompts that I would give to 18-year-old students in college became really hard to think about giving to these men. Every prompt I would look at, and I would think about, “Describe a difficult choice you’ve had to make in your life.” Which is fine for an 18-year-old, what kind of choice are they gonna talk about? But when you start to think about what these men’s lives have been like, and the kind of things that might come to the surface. Every prompt became problematic, every prompt became troubling.

Do we want to think about what life is like happening outside? Do we want to think about their lives on the inside? What do I want them to think about? Is all of it going to be traumatic? And so that has been really hard, but I’ve learned that things will come to the surface for some of them, and it won’t for others, and some of them want to write about these hard things, and some of them don’t. And if you give them enough freedom and flexibility to write about whatever they want to write about, when they want to write about it — one moment they might want to deal with these things, the next moment they don’t want to deal with these things. And to let things just happen, right?

JS: It does seem challenging, because when you’re writing from life inevitably traumatic experiences come up, but you want that to be voluntary or–

AK-L: Exactly.

JS: –not like a therapy class necessarily?

AK-L: Absolutely! I believe 100% in the power of writing to be therapeutic, but I’m not a therapist and they’re not therapy classes. So yeah it’s this really fine line between giving them an opportunity to write about things that they feel and want to express, and also knowing that there might be some lines that we come dangerously close to. That we’re not prepared to talk about in class. I’m not prepared to facilitate a discussion of those things.

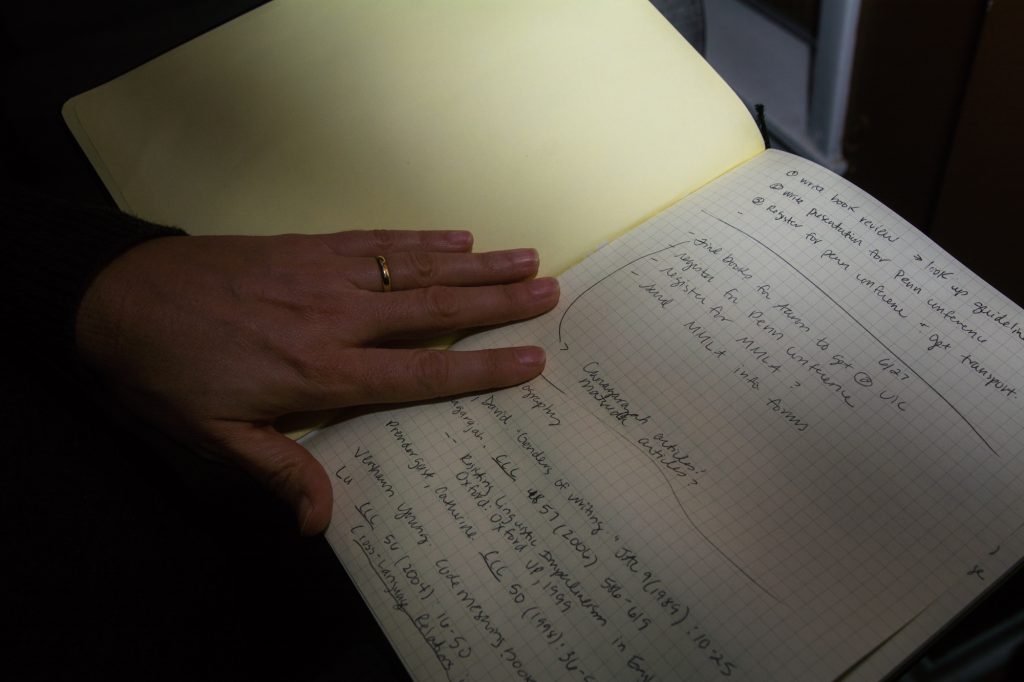

Image: Aimee Krall-Lanoue’s hand rests on a opened graphic paper notebook with a variety of lists and book citations. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo.

JS: So you got into this a little bit already, but can you talk about what the average class is like? What you’re saying is, the structure changes every day?

AK-L: Kind of, I mean so basically we go in, we ask if they have writing they want to share. Sometimes that will last an hour, sometimes it will last 40 minutes, depending on who comes. I think we have 13 guys on the roster. But I think there’s been times when we’ve been down to four guys who come to class because yoga was happening at the same time. And so in those times when we had a full class, we could spend the whole two hours with them just sharing their journal writing. Because initially I would come in with six journal prompts that ideally I tell them to write one a day, so that they keep writing every day. But if you don’t like a journal prompt, don’t write about it.

Sometimes there will be prompts that a lot of people gravitate to so they’ll all just feed off of each other. Someone will read theirs and someone will say, “I also wrote about this, but this is what I wrote,” or someone says, “Well I wrote that, but I took it a different way. This is what I wrote.” Sometimes somebody will say, “I didn’t like any of those journal prompts, so I wrote this.” And then sometimes somebody will say, “I went to this other one from a few weeks ago that I didn’t write about but I wanted to write about it.” And then we’ll do that for a long time. And then we’ll get to a point where maybe I’ll pull out something that I brought to read, a piece of published writing that we’ll read and we’ll talk about for a little bit. There are at least two guys in the class who are working on novels. And especially one guy would read every week 20 minutes from his novel. He’d read a chapter.

JS: That’s awesome.

AK-L: Yeah it was really awesome. And so that would be the kind of thing we’d do at the end of the class, we would say, “Where are we at? Let’s read, what’s happening next?” Sometimes I will plan some more sort of skilled stuff where we’ll look really closely at language. So I’ll pull out quotes from different pieces of things to look really closely at. So look at how this sentence is structured, look at the words they use, what else could they use here, why do you think they used this word. One time we talked about some post-structuralist theory, we talked about language, and representation, and symbolism. So it kind of just depends who’s there, how many people are there, if they want to talk and write about things.

JS: In a lot of ways it feels like the space of like, when you start to write or make art, has to be this non-judgmental, open space that’s very opposite the environment of a jail — do you find it difficult to create an environment that is like that in a really chaotic larger environment? What do you do to foster that kind of environment?

AK-L: I think that’s actually very interesting. Because there’s also this sense of the jail being very controlling, right? Regimented and strict. There’s also this sense of it being very isolating. They’re separated from everyone that they love. They’re there on their own. The boredom, right? The day-to-day sheer boredom of what they have to do. So it creates this internal space, where they’re so internal in thinking and in their own worlds.

The ways that I think we had to disrupt the jail space have come up in odd places. So I think that they have come up in places where they want to write something that they feel is controversial, or they want to write something that they feel people might take the wrong way. They’ll be very self-censoring about things. And we’ll have to say, no, actually, keep writing this. You can say what you’re saying, you’re not saying anything that’s offensive, you’re not saying anything that isn’t true. But also, because it’s writing, it carries with it this huge stigma about what’s correct, and how you do it. And so mostly I think what I have to do is I have to get them to stop being so judgmental of their own work. And of each other. What you’re doing is great. Because you’re doing something, right? And what you’re doing is — it doesn’t have to do these other things. So it’s almost like the self-imposition on themselves is almost stronger than the jail’s imposition, the jail’s confinement.

JS: Have you encountered actual censorship in terms of what the people are allowed to say or do in the classes?

AK-L: I have not. But I know that it’s there. And I know that I have no doubt that there are lines that we could absolutely cross, that would put what we do in real jeopardy. So I just try to be really careful about the prompts, like giving them prompts that steer them away from doing anything that might cross lines, might be overly critical. Not just critical, cause they’ve written things that are critical of the jail. Or critical of the system, all those kinds of things. I think that that’s fine. I don’t know that anybody has a problem with that. I think that if it becomes inciting in some sort of way it would be a problem. And that’s where the line gets sort of blurry, when does it become inciting?

So in all of our classes we have the men, and then we have a correction officer in the class with us. And so there have been a couple of times where there’ve been these moments of guys talking about what it’s like in there, and the ways that they feel, and the ways that they’re treated and this sort of strange sense of, here is this person on the other side, sitting there. One time I think maybe a couple classes ago, Billy [McGuinness] said, “Okay, well let’s talk about this. We’re not acknowledging there’s this correctional officer right here. What do you think about what everyone’s saying?” And there was this amazing moment where one of the guys who was talking about what the jail does to them and how the whole system drains them and really beats them down. And he said, I can’t remember exactly how he phrased this, but he said, I’ve treated this officer at first really badly, because I thought that he was just one kind of guy. So I treated him terribly and I was making life really hard for him. And then I realized that he was a good guy. He wasn’t this other kind of guy. And so he apologized, he said I’m sorry I did that to you. Do you accept my apology? And the officer was I think kind of struck by it and was like, yes, you know, it’s just a job, it’s okay. But it was a really crazy moment of acknowledging all that was happening there.

JS: Right, like people had been operating as symbols for larger systems as opposed to acting as individuals.

AK-L: Yeah, yeah.

Image: Aimee Krall-Lanoue sits at a dark wood table with her hands folded in front of her, smiling slightly. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo.

JS: So you also got into this a little bit but you mentioned people write novels, and I was wondering if you have specific practices or pieces of writing that you remember and you’d feel comfortable talking about?

AK-L: There’s been lots of poetry. Poetry that has woven people’s real lives with larger historical themes. So there was one guy who was writing poetry about — I think he was going off one of the prompts — he was writing about freedom. What freedom is. So he was writing a little bit about being in the jail. He was writing a little bit about growing up in Chicago, and growing up poor in Chicago, and growing up in the inner city of Chicago, and not following in his father’s footsteps, wanting to be different from his father who had also gone to jail, and had felt abandoned by his father. And then he moves into talking about his son and wanting to be a different person to his son than he was to his father. His son is now in college and his son is making it. And then going all the way back to ideas about freedom, and really going back to slavery and this position that created this life that he has now. Understanding that there’s this life and these choices that he’s made, but also that’s part of this bigger thing that’s beyond his control and beyond his choices. And that was pretty amazing. That poem was really amazing.

And then the novel that we’ve been hearing pieces of every week. It’s an urban fiction novel, with some supernatural elements. And it starts off with a professional team going into a house to rob it and things get really crazy really fast. And that was really really great. Every chapter he would read was fascinating to see where it was going and what was happening. And then there’s been people who wanted to write about their lives, so have wanted to tell memoirs about who they are, where they came from, how they got to where they are today. There’s somebody else who’s writing a novel about weird things happening also. It’s not supernatural but there are other weird elements coming into it. There’s been some zombies, people writing about zombies. So it’s all them and their imaginations and all these pieces of history and it’s fascinating.

JS: So of all things you could teach at Cook County Jail, why art? And do you think that art making has restorative or writing has restorative, healing, inherent properties?

AK-L: Oh absolutely, yeah. Because writing is thinking. And so we tend to think of writing as being a transcription of what’s in our heads, right? We have these ideas, we have these thoughts and put them down on paper, but it’s not actually what writing is. Writing makes writing. Writing changes thinking, and writing changes how we understand something. We come to learn and know things through writing. We don’t know things and then we write about it, always, we write and then we know.

So, the opportunities I think for these men to write through some of the things that they’re feeling, write through some of that trauma, is evident. And they will say I started to write about this one thing, or I started to write about my dad, or one guy was writing about how he felt he was a failure, he failed at everything. And here he is in jail as the most obvious example of his failure. And I was asking him well did you, how did you feel after you wrote that? And how did you feel now reading it, not just how did you feel after you wrote it but how did you feel now reading it? It’s this thing that is now on paper that is separate from you. And he said, “It did make me feel much better.” To have it out. There’s something to this idea of getting it out, of it being here and it’s no longer only in him. And I think also the idea of sharing, it is so important. And that was sort of really where I started all this, which was this idea of sharing writing. And that’s something I have strong interest in doing research on and studying as it’s about the sharing, not just about putting it down and getting it down on paper. It is about the sharing. And somebody else reading and encountering it, that I think is also transformative.

JS: Is there anything else that you feel is important to talk about? Or are thinking about right now?

AK-L: I think the thing that I’ve been most struck by is that for some of these guys it’s just so, I guess ironic, deeply, terribly ironic, that jail became the only safe space for them to become these writers and readers. That there was no place for them in this world and in this city, where they could even write. They had to go to jail to be able to do that. And that’s shocking and unbelievable to me that this is the place. They have to get behind bars in order to have a life or a world where they can do this, because they can’t do it out in the world. And they talk about that, they talk about how it’s not just about the distractions but it’s about this world that we’ve created for these men that doesn’t give them any opportunities or options to be anything other than what we have sort of turned them into. And I think about the privilege, the unbelievable privilege that I feel to be able to hear and to be able to read what they have written. It just — I get let into them, right? I get let into their lives and their thinking and that’s, I think that’s something we undervalue as a culture, how profound that is. Somebody’s letting me into their thinking. It’s huge. There’s no other way to do that.

This article is published as part of Envisioning Justice, a 19-month initiative presented by Illinois Humanities that looks into how Chicagoans and Chicago artists respond to the impact of incarceration in local communities and how the arts and humanities are used to devise strategies for lessening this impact.

Featured Image: Aimee Krall-Lanoue sits at a dark, reflective wood table, her head propped up by her arm. She is wearing a dark sweater and looks thoughtful. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo.

Jordan Sarti is a writer and journalist in Chicago. Her writing has appeared in In These Times, HYSTERIA, Temporary Art Review and Slutist. Right now, she is thinking about body politics, carceral capitalism, and plants. In her spare time she invents increasingly intricate ways to rest.