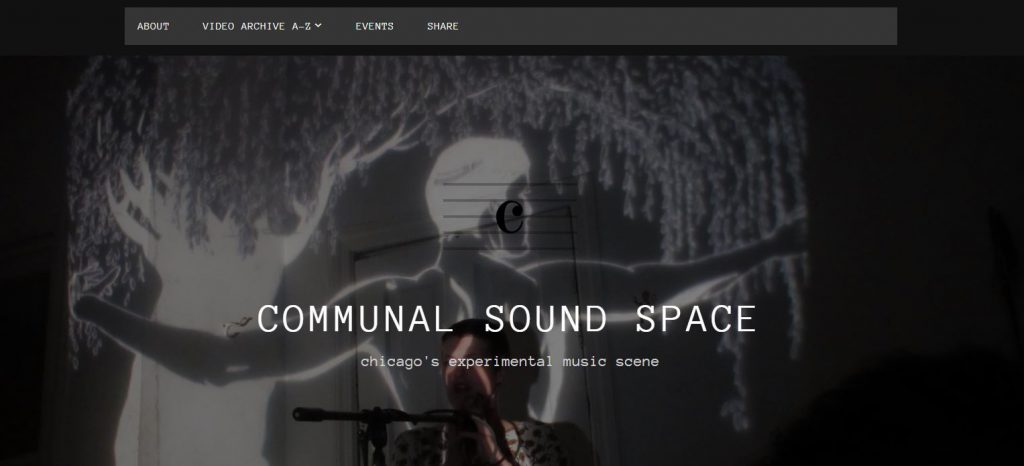

Communal Sound Space

An interview with musician, storyteller, and Chicago Public Library children’s librarian–and a curated video playlist from the archives.

Erica Mei Gamble is a musician, storyteller, and children’s librarian at the Chicago Public Library. These roles converge in her ongoing project Communal Sound Space, an ever-expanding collection of video footage of DIY music and performance in Chicago. Since the launch of its online presence in August 2017, the archive makes public hundreds of videos documenting nearly a decade of performances in DIY spaces and small galleries around the city.

The project amounts to a deeply personal history of Chicago music. Erica has filmed each performance herself, setting up shop at a good angle. Watching her record has become part of the fabric of going to a certain type of show: intimate, experimental, and for the most part, ephemeral. Thanks to Erica, that last bit is changing. Anyone curious about what goes on after hours in the darkened spaces of Chicago can now experience—or pause, rewind, and relive—a slice of it from anywhere in the world.

I caught up with Erica about her project—creating safe spaces for expression, the impulse to document, maintaining an archive as a constant work in progress—and invited her to curate for Sixty a selection of videos from the archive that demonstrate the scope and diversity of her project.

Nina Wexelblatt: The name of the archive, Communal Sound Space, is the first thing you see when you visit the website. It really sets the tone, and seems to apply equally to the close-knit DIY music scene and your online record of it. How do you think about communal space online or offline?

Erica Gamble: The IRL and online sound spaces [in the archive] incubate and facilitate artists who contribute to the DIY culture. My favorite IRL spaces are the places where people who are typically marginalized and oppressed by a moneyed police state can feel safe to dance and celebrate each other. These sanctuaries are built by a dedicated DIY community and actually demonstrate how peaceful, radical, revolutionary anarchy can exist in the world. Our efforts are labors of love, which is obvious when you see a space transformed by visual artists and sound artists performing their music live for little to no monetary compensation.

NW: Can you tell me about what you think creates or defines this community? How do you decide what to include?

EG: The community I follow is built on a foundation of love and light with no tolerance for fascists; I’ve seen this community call out abusers and people who demonstrate hate and intolerance. Alone, I dare not define this community; it is shaped by the people who contribute their energy by letting their creativity shine out and by showing up in solidarity and support.

Most of the shows I attend are a result of the friendships I’ve developed over the years. With this DIY community I’ve traveled to lucid dream-spaces and magical realities. The friends I make in those dreamy places have inspired me to create and contribute in my own forms. Expressing myself creatively is an urge I’ve always felt necessary to act upon. When we create, we become the Creator. In this nurturing community, I feel that these creative urges are continuously celebrated. Behold our creations! As a simple offering to the community that sustains creative souls—no simple task—I record as much as I can. I am more enthusiastic about documenting femmes, queers and POCs because our voices are powerful and notable, and our expressions should have a platform.

NW: When did you start recording this—your—community?

EG: For decades, I’ve watched friends performing in small galleries and DIY venues. Starting in 2010, I made efforts to record when my closest friends were performing, if I had my camera and the music moved me. The first show I filmed and uploaded is of Chip Chip Chippewa at Buzz Cafe, featuring my partner Alex Beam, Adam Rahn, and Dylan James. Alex and Adam joined our filmmaker friend, Jason Ogawa in a music project called Th’ Tarnation Boys, later called Tarnation. I adored Tarnation because all the members were like family to each other and to me and they were making sweet music together. I continued to document my dear friends’ performances and, occasionally, rehearsals for my personal entertainment, and because some [musicians], particularly Carlos Chavarria, also told me it helped them to write and improve their music. Then I started recording a few of our favorite electronic music artists performing in Chicago, like our favorite project, Excepter.

NW: What do you find important to capture when you’re recording?

EG: Sharing photos and video with my community of friends strengthens loving familial bonds, or is at least good for a laugh. Taking photos only captures what that meaningful moment looks like – but to see and hear that performance again became so important to me, because it’s a moment that will never be replicated.

NW: A lot of DIY shows, especially the kinds of shows you film, are pretty experiential by design. Video lets you capture the performative elements and visual artists who contribute to these shows, too.

EG: If I’m awake and aware, I’m considering the visuals created by visual artists as I record and tag videos. If someone is manipulating video live, I try to get them in the shot at least for a minute. Information about visual artists collaborating with sound artists is mentioned in the description of the recording. Sometimes I know the visual artist and it’s easy to credit them in the description and tags. Any visual artist who’d like credit in a recording on this archive need only message me about it.

NW: Does the activity of recording change your relationship to the events you attend?

EG: Recording is certainly work, but I try to be as quick and noninvasive as possible. My favorite method nowadays is to set up a tripod–my “spyder”–and let the camera do its thing, so I can be more present in the moment. I used to feel shy about recording, because when there’s a camera present, people may get nervous, and it might affect their behaviors or their performance. I’m still shy about setting up the camera in case it ends up in someone’s way or if I think I may be disrupting the private atmosphere of an intimate DIY show. However, after years of being that person with the camera, many people are used to seeing me playing with my tripod, batteries, and SD cards.

I’ve also met other DIY documentarians at these shows. Collaboration is an important practice to me because learning from and experimenting with others is what my life and my DIY community is all about. I remember an impromptu, one-off collab with Ed Bornstein at a Horse Lords show at Situations; he brought out this professional equipment and while he held the camera, I held this external mic and interviewed people who were there to hang out and see live music.

NW: Even when you set up a tripod and leave it to go dance, you’re experiencing the show in a different way from the people around you.

EG: I used to hold the camera for 20-30 minutes at a time until my wrist started feeling stiff. Just recently, I set up a tripod on a table behind the space where I was dancing and three minutes later it fell right on me and another innocent dancer–sorry! My best friend once remarked during a performance, “I’m surprised you’re not recording.” Seems people are expecting to see a camera if I’m around.

NW: Your relationship to the project and this community is so personal. Why make the archive public?

EG: Musicians are doing incredible work here. Just because it happens underground doesn’t mean it needs to stay buried there. I maintain a public archive because access to live music from Chicago should not be prohibited because you live elsewhere. A few local musicians have told me they like to share recordings of their performances with faraway friends. Oftentimes, where you live geographically within Chicago can be prohibitive to attending live performances, too. I definitely don’t see enough live music on the South Side. By organizing a public archive, I’d like to inspire others who take photos and videos to share ideas or content with this archive or in their own way. I love seeing other documentarians uploading from their DIY music communities.

NW: You’ve mentioned drawing inspiration for the project, or at least the public archive, from local history. There are certainly precedents for documentary work in the Chicago music scene, from Plastic Crimewave to Malachi Ritscher and beyond.

EG: I remember seeing Matt [Kimmel, of Acid Marshmallow] at shows. He’d would stand with his camcorder in hand and sway to the music. I visited his website when it was live and he was hosting all his videos independently; now the Acid Marshmallow archive lives on Vimeo. In 2015, people were mourning the passing of DIY scene supporter and documentarian, Ray Ellingsen. He was working on a book! I’d love to see that book. I’ve listed a few other Chicago/experimental music archives and archivists on my WordPress About page. I’m definitely wondering which femmes are (unintentionally) missing from this list.

NW: Thinking about history, archives, and systems of organization, you studied library and information science in graduate school. How does your work as a librarian influence the project?

EG: As a librarian, my work is to serve my community: to help it grow and to celebrate it for what it is. I upload videos as quickly as possible. I just cannot horde all this data on my devices, so the videos live on YouTube. It’s not ideal, but it’s free and accessible. When the number of videos I had uploaded grew to over 400 with no system of organization, the librarian/information scientist in me felt compelled to organize all this data. I set out to organize all public uploaded videos of sound performance artists alphabetically. My practice of archiving involves adding a little metadata to make things easier to navigate and locate.

In August 2017, I started a WordPress site as a simple method of organizing recordings. I’m happy to admit it is not perfect, doesn’t meet digital archive best practices, and is a work in progress. But many local experimental artists like to link to my recordings of their music to promote their work, because it’s free to share and recordings may not exist elsewhere.

NW: The question of uploading permissions could be tricky, especially in a DIY community that doesn’t necessarily make money off of these performances.

EG: Something I’ve always felt a little shady about is that most of the content I’ve uploaded is other people’s work–their life’s work! I’ve noticed that if audio from a performance matches a record label’s copyright material, YouTube will monetize the video on behalf of the copyright holder. I would never dream of monetizing these videos for personal financial gain. Also, ads on videos suck! Often, I’ll let artists know that I’ve recorded a bit of their performance and that I’ll share it with them once it’s uploaded. I ask artists if they want the video to be unlisted, if they would like edits made to the title, if there are any links they want added to the description. All artists featured in the archive are invited to let me know of any details or settings of a recording of their work they would like to be adjusted.

NW: Have you encountered other big challenges?

EG: Before I had extra SD cards and got a camera that uses rechargeable AA batteries, I had to be more strategic about who and when I would record. This was especially true when I’ve attended Voice of the Valley, a three-day music festival in the Midwest where musicians and followers of music travel from all over to camp in nature and celebrate experimental music. I would typically record as much footage as possible of [musical] projects like Telecult Powers, Profligate, and Chemtrails. I’ve had to cut recordings short because of the limitations of my old equipment.

There have been moments when I wonder to myself how long I’ll keep recording and uploading live performances and who would care if I stopped, but those thoughts arrived during darker tech times before my gear situation improved and my process grew a little smarter and more streamlined.

NW: Your new camera and recorder suggest you’re in this for the long term.

EG: Investing in a new video recorder–a Zoom Q2n, designed to record live audio–was a definite decision to rededicate my efforts to this video archive of this DIY music scene. It wasn’t too difficult a decision, because I’ve received a lot of gratitude and positive feedback from artists in the archive. Some artists have expressed that they consider this recording, uploading, and now organizing work I do to be a service to our community. It is my pleasure to provide this service.

Featured image: Artist and archivist Erica Mei Gamble looks into the distance outside Harold Washington Library in downtown Chicago, where she works as a children’s librarian. Photo by Ryan Edmund Thiel.

Nina is a Chicago-based writer and curator interested in the intersections of art, ecology, and technology. She is the current Curatorial Research Assistant at the MCA Chicago. Nina earned a BA from Yale and MA from Williams College. You can follow her on Twitter @nina_rrose.